101 ~ Lost in space

I have a confession. This forager and wildlife conservationist is distinguished by having the worst sense of direction of anyone I have ever known (at least among those for whom I have a sense of their sense of direction). The navigational part of my brain seems to have gone missing at birth, and I am so far to the left on the bell curve of direction finding ability that I risk bumbling off the edge of the earth. Nearly everyone can find their way back to camp, or to the post office in town, better than I can.

Indeed, this is an odd deficiency and something of a handicap for a hunter and forager, and someone whose day job is to search for rare animals in the forests of Southeast Asia. It’s also a bit odd for the son of navigator – my father served in World War II as navigator on a B-29 long-range bomber over the Pacific, and as far as I know never got his plane lost. Maybe the ability skips a generation (or in my case, leaps over one). In any case, this apple fell pretty far from my father’s navigational tree.

A few weeks ago I was reminded yet again of my deficiency while in the woods near the house with my new housemate, Grant, searching for a deer I had wounded late in the afternoon. To be fair, dark had fallen and we were probing the woods with flashlights. But this corner of the woods covers only about 30 acres, and starts just behind the house. I have hunted it and searched it for morels and tapped its maple trees for the more than ten years I’ve lived here. In contrast, Grant had never been in this corner of the woods. At one point, I felt I was leading us away from a familiar landmark, a tower of sandstone just several minutes’ walk from the house. To my surprise, we soon came upon another tower of rock... Er, no, it was the same one – we had been walking toward it from the other side, not away from it.

Half an hour later, after reorienting from the rock and marching confidently on, I announced to Grant that I was looping us back toward the house. “Um”, he said, pointing in the opposite direction, “Isn’t the house this way?” “No, I don’t think so”, I replied, with a bravery of voice that masked a creeping, familiar queasiness. Grant consulted his phone, found reception and a navigation app, and sure enough, we had to turn around and walk nearly 180 degrees opposite from where I was about to take us.

This is typical. It’s as if my brain’s navigational apparatus isn’t exactly missing, but its poles are reversed. I know the way, but I am invariably wrong. If I say camp is “thatta way”, turn around, dear reader, walk in the opposite direction, and you’ll soon be enjoying a cup of something warm by the campfire.

In my early twenties I lost my way metaphorically and spiritually, and took a break from the University of Wisconsin. Some months later I found myself in the backcountry of Idaho, on a three-week training course for professional hunting guides (this was the pre-GPS era, when life was map, compass and moss on the north side of a tree). At the conclusion of the course we graduates were offered fall placements with local outfitters. But the three weeks had confirmed in me enough about my wilderness navigation skills (none) to impart the good sense to decline any job offers. I saw no point, nor any anticipated pleasure, in getting wealthy hunters from Chicago lost in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (instead I returned home and finished school - where I sometimes had trouble finding my classrooms, and not just on the first day...).

In the film “The Edge”, Anthony Hopkins’s character, who is lost in Alaska with two others, observes, “Most people lost in the wilds, they die of shame” (watch the scene). I knew exactly the meaning of that line when I first heard it. More than once I had experienced the shame of incompetence from losing my way in the woods, a shame that can then stimulate a rushed response to get unlost as quickly as possible – with the predictable result of getting lost even further. As Hopkins’s character knew, the shame and frustration of getting lost can rush us into poor decisions, or cause us to give up in resignation and defeat – and neither is the one response that can best help: thinking calmly on a solution.

Another film that, unfortunately, often comes to mind when I start to feel disoriented on what I thought was familiar ground, especially as dusk is falling in the woods, is “The Blair Witch Project”. It’s a most creepy one, where you’re right, you shouldn’t be lost, but an unseen, malevolent force is screwing with you and leading you further and further astray. Good luck thinking your way out of that one. That film did for getting lost in the woods what “Jaws” did for swimming.

Perhaps all this explains, at least in part, my deep resonance with stream trout fishing. A stream is a one dimensional landscape, just upstream or downstream, and so it’s nearly impossible to get lost. As long as I can walk from the road where I’ve parked to the stream, and back again, I’ll be fine, and even I can usually do that. Or, just park and start fishing at a bridge over the stream; not even a Blair Witch could readily muddle that up. My direction-finding deficiency might also figure into my affinity for the Driftless Area, given that hilly regions hold an ever-available solution when lost: simply walk downhill, since all slopes eventually lead down to streams, and all streams lead to roads.

In any case, we can be quite sure that I did not pass one of my former lives as a homing pigeon. Nor as a member of the Guugu Yimithirr tribe of northeastern Australia (note: I almost typed, in my abiding confusion, ‘northwestern Australia’). Guugu Yimithirr people use a system of orientation based entirely on compass directions, to the extent that, remarkably, their language has no expressions for ‘left’, ‘right’, ‘front’ or ‘behind’. A Guugu Yimithirr person would not – could not - say, ‘Please pass me that cup, the cup to your left’, but would say ‘the cup to the south’. Nor would they shout, ‘Watch out, snake behind you!’, but ‘Watch out, snake to the east!’.

As you can imagine, Guugu Yimithirr children learn early, as a second nature, to be ever-aware of their position in relation to the world, not independent of it, and how the world surrounds them. A Guugu Yimithirr person always knows which way is north. In contrast, for native speakers of English (or German, French, Spanish, Italian, etc.) whether something is to the left, right, behind or in front of me depends only on my orientation, independent of the world. It’s all about me – which seems a bit lonely, truth be told. It can also be woefully unhelpful. If I’ve lost track of where I am in the woods, knowing which way is right or left will not be particularly beneficial.

There is, I think, a parallel in our emotional or spiritual lives (choose the adjective that best suits you). We can feel lost when we rely too much on ourselves, or insist that the world orient to us. In fact, I can’t know where I am – or where to go – by just looking in the mirror.

And so my New Year’s resolution is to be more Guugu Yimithirr-like. To be in the world, and pay more attention, with head up, as I move through it. And if (er, when) I do get lost, in the woods or in my soul, I can at least try to find calm and acceptance there. That, like finding home by walking downhill, is always available.

And may you, dear reader, find a path toward ease and prosperity in 2024. Happy New Year!

What I’m watching and can recommend:

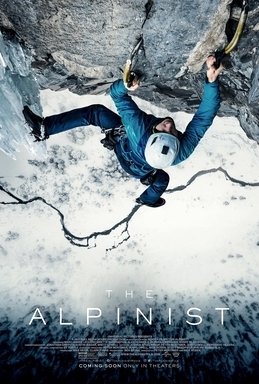

I recently watched “The Alpinist”, an extraordinary 2021 documentary about the young Canadian rock and mountain climber, Marc-André Leclerc — a one-of-a-kind talent, and soloist, with no interest in the limelight. It’s a fascinating 90 minutes.

Course announcement:

Please join for me at the farm on Saturday, March 9, for a one-day workshop on making maple syrup. We’ll have fun (and I promise to not get us lost). The event is offered through Folklore Village, with details and registration available here.